The curious history of animal crackers

Do they symbolize ancient pagan rituals or are they just fun foods to play with?

If you’re reading this on Substack, please update your links and subscriptions — we’re on WordPress now!

I’m posting here on Substack for the first time in several months because I can see that a bunch of people follow the newsletter here, but don’t subscribe to the newsletter, which is now hosted on WordPress. (I moved there back in January.)

It’s confusing to be in two places and I’m sorry about that. I left the Substack site up just so old links would take you somewhere, but I realize that also makes things more complicated and … here we are. If you’ve been missing out, please join the feast over there, and my apologies for the lack of snacks you so richly deserve.

All of which is to say:

You can read a preview of the latest post below (it’s a good one!), but then you should go read the whole thing over at the new Snack Stack.

While you’re there, catch up on all the latest content you may have missed, including posts on SpaghettiOs, snacking in bed, and “extra mild” salsa.

When you read the full post, hit that subscribe button so you don’t miss any other sweet/savory/salty/tasty content. Most free subscriptions should have already transferred; WordPress won’t let me switch over the paid ones.

Email me at doug@douglasmack.net if you have any questions or if there’s anything I can do to help. This is a one-man operation, so I appreciate your support, readership, and patience as I continue to figure out how to make this the best site it can be.

Generally speaking, I’d prefer that my kids not play with their food. Every now and then, though, I don’t just encourage it but expect it.

Exhibit A: animal crackers, a food that exists far more for entertainment than for consumption. You cannot just scarf them mindlessly; they aren’t Cheetos. Even if you’re an adult, you’re all but required to pluck the crackers from the box, one by one, and play. Make little elephant-trumpet sounds before nibbling off Dumbo’s ears (sorry, dude). Stare down the bear for a long, fraught moment. If there’s a kangaroo, bounce it on the tabletop already—you know you want to.

If that’s not your style, find another snack. You’re not eating animal crackers for the flavor, are you? It’s all about playing and crafting a little narrative while you eat.

Consider, for example, that animal crackers’ most famous iteration is in a box that’s meant to look like a circus train, because when the packaging was introduced a century ago, circuses were the epitome of kid entertainment.

Consider this Jell-O ad from Life in 1956:

Do we think the animal crackers are contributing to the flavor of the dish? Or do we think they’re soggy sludge that’ll fall apart the moment they’re spooned out?

All of this was my first thought when the excellent writer Kelsey Atherton suggested I investigate the origins of animal crackers. They’re fun! I said to myself. People have always loved animals! Is there really more to the story?

I’ve been doing this long enough to know that there’s always something deeper and intriguing when you start looking; that’s kinda the whole point of this newsletter. But I still have my doubts at the outset sometimes, as my natural cynicism does battle with my natural curiosity.

Down the rabbit hole I went, following various twists and turns that took me back centuries and, as often happens, mostly made me more confused.

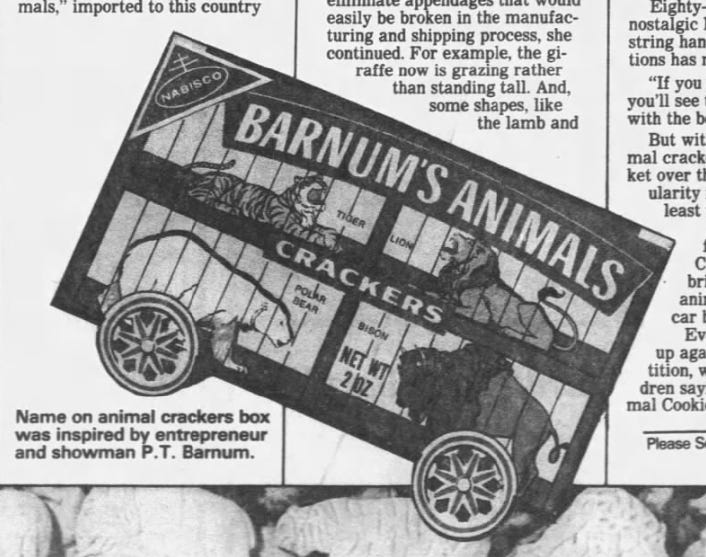

The history of animal crackers has been a popular topic for news articles over the years, usually in honor of some major birthday for the Nabisco version of animal crackers (the article clipped above marked the brand’s eighty-fifth year).

The Nabisco product debuted in 1902 as Barnum’s Animal Crackers, an early pop-culture-meets-food brand collab (in exactly the same vein as, say, today’s Baby Shark fruit snacks or Bluey Biscuits). They started as a short-term promotional item, with the animal-adorned box intended to be hung by its string as a Christmas tree ornament. People loved it, and within a month of releasing the product, Nabisco had sold out all 189,000 boxes and decided to make this limited-edition snack into a permanent part of its lineup.

But Barnum’s Animal Crackers weren’t the originals. In fact, it’s not even accurate to say that they popularized the concept of animal crackers, because there was already a different brand: Stauffer’s Cookies, which started in 1871 and still exists (these days, they’re best known for their iced version).

It appears that David Stauffer was the first person to sell a product called animal crackers, so we could say the story starts with him. But it’s not really the name that matters, is it? And long before Stauffer got to the specific terminology, there were all-but-identical versions in cracker-like formats (cookies, biscuits, etc.; please don’t make me dig into the differences between them right now, stay focused, people).

So let’s go back even further.

When you go looking for the predecessors, the things that might have inspired Stauffer in the first place, you end up at something called Springerle, a type of German cookie.

According to the many (many) other histories of animal crackers on the internet, Springerle was originally part of a religious ritual. Here’s a representative telling of this story, from Mashed:

The custom of shaping cookies to resemble animals has been traced back to at least the 17th century, where they were part of a midwinter festival and previously pagan religious observation known as “Julfest”, according to What’s Cooking America. During Julfest, it was common to sacrifice animals to the gods, who would in turn hopefully offer up mild weather and good crops. However, poor people faced a dilemma — they couldn’t even pretend to sacrifice their valuable agricultural animals, so instead, they gave offered animal-shaped bread and cookies in their creatures’ stead.

So that’s an intriguing twist. Animal crackers are not just fun and games! This is why we do the research, friends.

Obviously, I needed to know even more.

Even understanding that religious rituals come in many forms and I really shouldn’t laugh at them, it was hard not to be amused by the idea of this two-pronged ceremony. I imagined it like a festival with the Wicker Man as the headliner and the Keebler Elves running a more twee, snack-focused event in the free tent off to the side.

As far as I can tell, every internet version of “the history of animal crackers” that references Springerle uses the same source: the What’s Cooking America piece that Mashed cited above. In theory, there’s nothing wrong with using the same data point over and over if it’s proven and trustworthy. But a single source is a red flag when it’s a random website not known for fact-checking or research or rigorous journalism. Still, let’s see what they have to offer.

The What’s Cooking America post is a recipe with the customary preamble, which is where you’ll find that mention of Springerle cookies as a stand-in for animal sacrifices, which Mashed and others have taken as official truth.

There’s no other citation in this post, although this “fact” does appear to be based on some research, because it is mentioned in earlier, pre-internet sources. Looking around Google Books, the Internet Archive, and other databases, I found passing references to Springerle-as-animal-substitute in random cookbooks like Favorite Cookie Recipes (1994) or publications like this 1985 edition of Pennsylvania Folklife:

So, okay, we have some older references to Springerle, the original animal cracker, being used in pagan rituals. But none of this felt remotely conclusive, just endless repetition of the same hearsay. Eating cookies and killing livestock just felt miles apart.

Let’s establish a few caveats here. Pagan rituals with animal sacrifices are a real thing (the wicker man history, separate from the movie, is genuinely interesting). Animal cookies are a real thing. They existed at the same time and in the same place. Also, there are plenty of other snacks with roots in ancient religious rituals (see, for example, the infamous “host cuttings” popular in Quebec). Also also, an outsider can never really understand how a religious practice works or what it means.

I get all that. I do. But this story still seemed unlikely to me, in a way that I couldn’t shake. It was hard to parse how a sweet treat could be considered a worthy sacrifice to an all-powerful deity, in lieu of an actual once-living, now-bleeding cow or sheep. I needed to see stronger evidence that these data points actually connected.

When we’re talking about stories that don’t originate in the USA, it’s generally good to use an innovative technique I like to call “look at sources published in the actual place where it happened.” This often requires tracking down information in languages other than English. Luckily, Google Translate is right there and if you search “Geschichte von Springerle” (history of Springerle), magic happens. You find a German-language website called Springerle.de.

Now we’re getting somewhere. First bit of history from that site:

The people of the ancient civilizations on the Indus, in Mesopotamia and Egypt began to decorate their pastries with molds. These molds were initially used as simple molds for baking together.

To read the rest of this post (for free, no account needed!), head over to the new Snack Stack site. Thanks!